Interesting Facts About The Tuskegee Airmen

General Benjamin Davis Sr medal ceremony with Tuskegee Airmen

The term Tuskegee Airmen is the designation given to the first African Americans to complete pilot training in the USAA (United States Army Air corps). Anyone, man or woman, military or civilian, black or white - who served at Tuskegee Army Airfield or in any of the programs stemming from the Tuskegee Experience between the years 1941-1949 is considered to be a documented “Original” Tuskegee Airman. Throughout the history of the Tuskegee Airmen over 1000 airmen were trained in this ground breaking program during WW2.

In reality, the history of the Tuskegee Airmen did not begin in 1941, just as the history of African Americans did not begin in 1941. The spirit of the Tuskegee Airmen began when 20-30 enslaved Africans arrived in 1619, at Point Monroe in Hampton, Va., aboard the English privateer ship White Lion. Likewise, the history of the African American soldiers’ dates back to the Revolutionary War of Independence in 1776, and I suspect long before that In February 2021, at a speech at the Pentagon, newly elected Vice President, Kamala Harris noted,” As you know, this is Black History Month. And while we celebrate that part of America's history every day, let us honor also today the black soldiers who fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill, A comment that she was criticized for on social media because she signaled out black soldiers. Even though some of the black soldiers were enslaved men fighting for the freedom of White Americans.

African American Revolutionary War Soldiers

After the victory in the War of Independence, next African Americans soldiers took up arms in the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, and the wars from the American Civil War, too World War1. Over 300,000 young African Americans volunteered for service in World War1 before the official draft began in 1917. Throughout each of the conflicts, the impact of African American military service was hindered by slavery, rigid segregation and Jim Crow laws along with a reluctance of the United States Government to train African American soldiers due to fear that they would leverage their skills and weaponry on their oppressors in the United States.

Civil War Colored Troops As Predecessors of the Tuskegee Airmen

Acceptance of African American soldiers saw a seismic change in the Civil War. The Lincoln administration wrestled with the idea of authorizing the recruitment of African Americans troops, concerned that such a move would prompt the border states to secede. The states that decided to remain in the Union, however, maintained the system of slavery were Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, and Delaware. Also considering the events that led a piece of the state of Virginia, to split from the state and form a new state called West Virginia, which in effect became a fifth border state. Not waiting for leadership from the Lincoln Administration, Union General’s John C. Freemont in Missouri, and David Hunter in South Carolina issued proclamations that emancipated slaves in their military regions and permitted them to enlist, their superiors sternly revoked their orders. By mid-1862, however, the escalating number of former slaves (contrabands), the declining number of white volunteers, and the increasingly pressing personnel needs of the Union Army pushed the Government into reconsidering the ban (like Washington had done in the War Of Independence). On July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Act, freeing slaves who had masters in the Confederate Army. Two days later, slavery was abolished in the territories of the United States, and on July 22 President Lincoln took this opportunity share with his Cabinet a preliminary draft of the Emancipation Proclamation.

In recognition of the contribution of African American soldiers during the deadly Civil War (186,000 served in the Union Army) on July 28, 1866, Congress passed an act reorganizing the army by adding four regiments to the already existing six regiments of cavalry and expanding the number of infantry regiments from nineteen to forty-five. The reorganization included the creation of six colored regiments designated in November as the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry and the Thirty-eighth, Thirty-ninth, Fortieth, and Forty-first Infantry. The new colored regiments were to be composed of African American enlisted men and white officers. Three years later, Congress reorganized the army again by reducing the number of infantry units from forty-five to twenty-five regiments. For the African American regulars, this reorganization changed only the infantry units and not the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry. The Thirty-eighth Infantry and Forty-first Infantry became the Twenty-fourth Infantry, while the Thirty-ninth and Fortieth were consolidated into the Twenty-fifth Infantry. These two new infantry regiments completely replaced the former Twenty-fourth and Twenty-fifth.

The African American soldiers that served in the west were dubbed Buffalo Soldiers by the Native Peoples they fought against. Several theories are abound as to why. One theory is the soldier’s hair was like that of a Buffalo pelt. Another, African Americans fought like wounded Buffalos. Either way the soldiers embraced the nickname and it stuck. The Buffalo Soldiers were assigned to different areas of the west. The Ninth and Tenth Cavalry spent much of their time in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and Indian Territory protecting citizens, mail and supply routes and battling hostile Native Americans, and outlaws. The Twenty-fourth Infantry served in the Department of Texas, Indian Territory, and the Department of Arizona, while the Twenty-fifth Infantry served in the Department of Texas and the Department of Dakota. The color barrier for African American soldier began to crumble in 1887. From their inception, the colored regiments were led by white officers. This changed once African American cadets started graduating from the U.S. Army Military Academy. Three African American graduates of West Point,Henry O. Flipper , John Alexander, and Charles Young, all served as Buffalo Soldiers. During the Indian Campaigns, eighteen African Americans were awarded the Medal of Honor.

Buffalo Soldiers - Predecessors of the Tuskegee Airmen

The role of Buffalo Soldiers took on an international flavor with the fight for Independence for Cuba from Spanish rule. The famed 9th and 10th calvary and 24th and 25th infantry divisions showed their valor in several skirmishes on the tropical island. The Army felt that African American soldiers could better cope with the tropical climate because of their African linage. This was the case of arguably the most famous battle of the Spanish American war. Called the most integrated battle force of the 19th century, the troops of the 24th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry fought up the slope of San Juan Hill along with White regular army regiments and the 1st Voluntee Cavalry (the Rough Riders) led by Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt. Twenty-six Buffalo Soldiers died that day, and several men were officially recognized for their bravery. Quarter Master Sergeant Edward L. Baker, Jr ., 10th Cavalry emerged from the battle wounded by shrapnel, but was awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroism. One young promising white officer, John J Pershing, said of the Buffalo Soldiers, Lieutenant John J. Pershing wrote, "They fought their way into the hearts of the American people." At first very complimentary, later, Roosevelt would later say, despite this praise, incredibly Colonel Roosevelt later wrote: "Negro troops were shirkers in their duties and would only go as far as they were led by white officers."

WW1 African American Soldiers

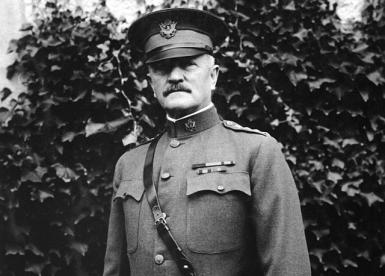

WW1 General John J. Pershing

The white officer who was closely tied to the Buffalo Soldiers was John J Pershing . In 1896 Pershing was assigned to the frontier with the Tenth Cavalry, an all-black regiment. Pershing was then assigned to teach at West Point. Here he was given the nickname “Black Jack” because he had spent time with the Tenth Cavalry. When the Spanish-American War broke out, Pershing was selected to command the Tenth Cavalry once more and led his men in Cuba at the Battle of San Juan Hill. The bravery and courage shown by the men of the Tenth Cavalry earned them Pershing’s respect and admiration. He often praised the black soldiers to others, an unusual thing to do during this time. Later in WWI, Pershing who would command the American Expeditionary Force, however, did very little to change the plight of his African American soldiers when it came to the prevailing segregation of the day. Pershing resisted request for his men to serve in Allied units. However, he had no such qualms about directing African Americans troops to serve under French command. The French certainly appreciated the contributions of the African Americans. More than 350,000 African Americans served in segregated units during World War1, mostly as support troops. Several units saw action alongside French soldiers fighting against the Germans, and 171 African Americans were awarded the French Legion of Honor .

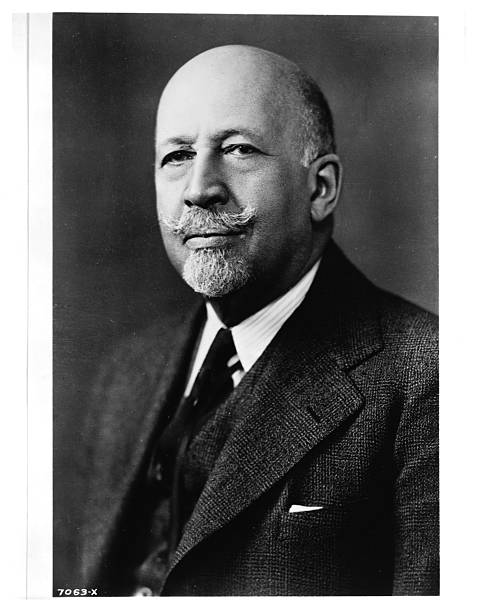

In 1909 a new organization emerged dedicated to ighting for the constitutional rights of Africans Americans, who were under sieged, in every segment of American society, at the dawn of the twentieth century. The NAACP (National Association For The Advancement Of Colored People). The group consisted of a racially diverse mixture of highly energized men and women ready to fight through the court system, and through education for people of color. Several of the original founders were acclaimed citizens of the day - Oswald Garrison Villard, Mary White Ovington, W.E.B. DuBois and Ida B. Wells-Barnett . The NAACP setup shop in New York City in 1910 and formed a board of directors. The first president was constitutional lawyer, Moorfield Storey. Through their masterful strategy of utilizing the law the NAACP would go on to be the preeminent civil rights organization in the world.

Moorfield Storey, NAACP 1st President - the Struggle for Equality Before the Tuskegee Airmen

W.E.B. DuBois - the Struggle for Equality Before the Tuskegee Airmen

The1925 classified War College report made it clear where the U.S. government stood, however, the NAACP saw the policy quite differently. Since the invention of flight, the flying experience had captured the world’s imagination. Men, women, and children looked to the skies at the wonderment of flight. African Americans were no different than anyone else wanting to experience the thrill of the day. The 1930’s would prove to be a watershed moment in the struggle for civil rights. Now armed with protenant NAACP and a African American press, the fight was on. Leading African American news papers of the day, The Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier had a nationwide reach, thanks in part, to an informal distribution network facilitated by railroad Pullman car porters who traveled extensively across the nation.

Army Chief Of Staff, General George Marshall shared his thoughts on the subject maintaining segregation when he said, “experiments within the Army in the solutions of social programs are fraught with danger to efficiency, discipline and morale….” However, President Franklin Roosevelt was beginning to feel pressure from all side as Europe was now engulfed in war, a 1940 re-election campaign and the African American press along with the NAACP were at his heels, in an attempt to end segregation in the military once and for all. Congress passed the Civil Pilots Act in 1939 to bolster a lagging pilot training system in the U.S. It didn’t take a rocket scientist to see that the German Air Force was a world menace. The act positioned the new agency to replace the FAA's predecessor agency, the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA), to expand an experimental program, authorized in December 1938, to train civilian pilots through educational institutions. The first signature court case against the Army Air Force would occur in Washington D.C., in January 1941. Based on the principles of the 1898 U.S. Supreme Court case Plessy vs. Ferguson’s "separate but equal doctrine, the Army Air Force had routinely denied African Americans cadet- pilot- training with an excuse that there weren’t adequate “segregated” training facilities for African Americans. A Howard University senior, Yancey Williams filed suit. The Armed Forces saw that the winds of change was blowing in a different direction now and agreed to allow African Americans to train as pilots albeit in segregated units.

the Dawn of the Tuskegee Airmen

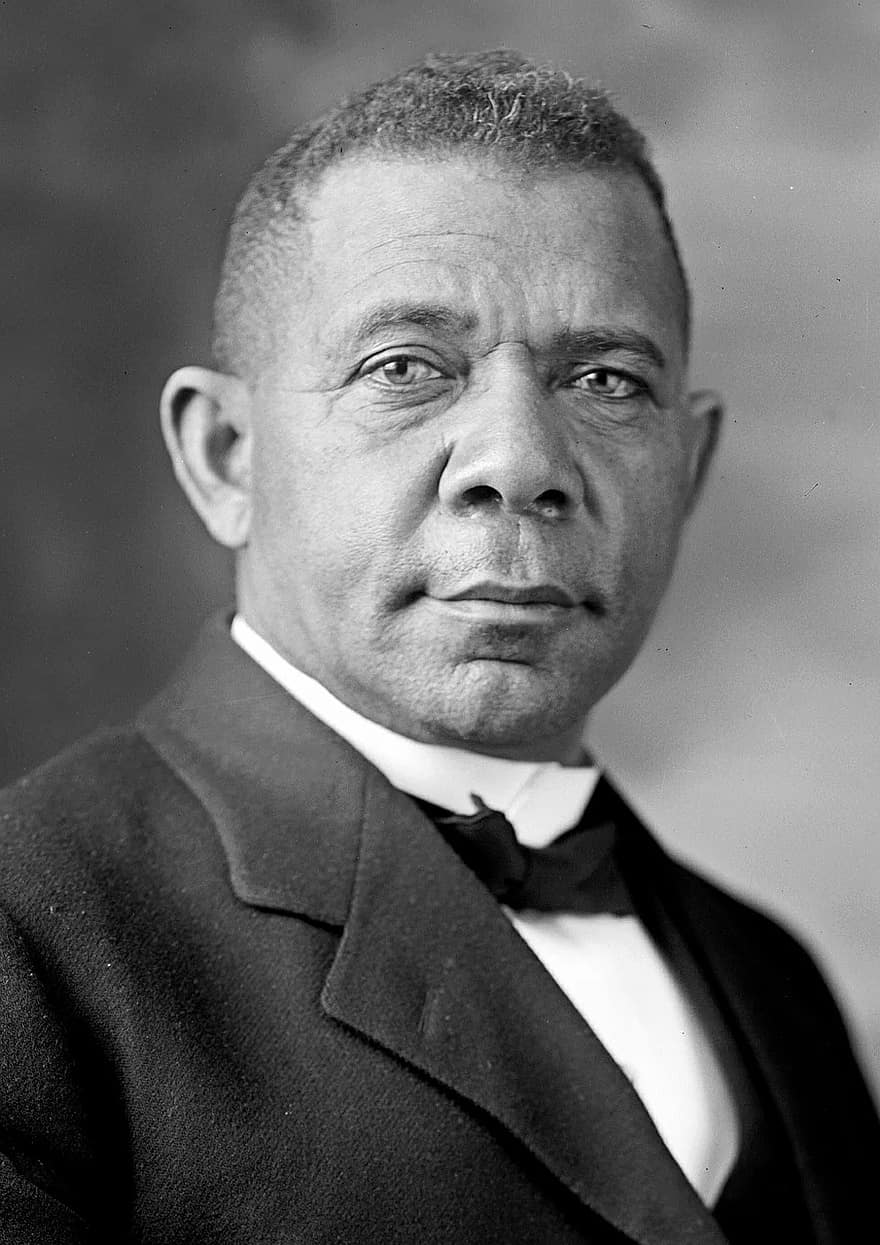

Booker T Washinton - Advocate for Independence of African Americans in WW2 - the Tuskegee Airmen Initiation

The college selected for the African American cadet training program was Tuskegee Institute. Founded by Booker T. Washington in 1881, under a charter from the Alabama legislature for the purpose of training teachers in Alabama. Booker T. Washington was an African American who advocated for self-reliance within the African American community. A policy not shared by other notable African Americans of the day, namely W.E.B. Dubois and Ida B. Wells. Many in the African American community who opposed Washington were more in favor of equality as the lynchpin for advancement of the African American community. Under the tutelage of Washington, the Tuskegee's program provided students with both academic and vocational training through a variety of degree and research programs. Acting quickly, the Air Force selected Tuskegee Institute, in Tuskegee , Alabama. Tuskegee was chosen as the place for the first African American military pilot training because Tuskegee Institute had an existing training program for African American civilian pilots, Tuskegee Institute lobbied and gained the contract to operate a primary flight school for African American pilots. Blessed with good flying weather nearly year around and of great importance to the Air Force, the area already had a segregated environment, which was consistent with the segregated training principles.

The burgeoning Civil Right community was certainly glad to have a hard-fought win in gaining access to pilot training for African Americans, however, in reality, it was still viewed as a half measure because the program would be done under the guise of hated segregation. The very first African American flying unit in U.S. military history was the 99th Pursuit Squadron, which would later become the 99th Fighter Squadron. It was first activated at Chanute Field, Illinois, in March 1941. In keeping with segregated practices, its first leader was a white officer, Captain Harold R. Maddux. The first pilots would come once the move was made to Tuskegee. The first soldiers to serve as Tuskegee Airmen were drawn from the Army’s existing troops, the 24th and 25th infantry were mobilized to set up operations in Illinois. An additional group was mobilized to begin ground support training. The long-awaited process for African Americans to begin OTS training (Officer Training School) while in Illinois. Five young African Americans were selected to be the first training cadets, and were from a cross section of America. Three were from the Washington, D.C. area, Elmer D. Jones, Dudley Stevenson and James Johnson, along with William R. Thompson, Pittsburgh and Nelson Brooks, Illinois. All completed the difficult course and were later commissioned Army Air Corps Officers.

Dr Robert Russa Moton, 2nd President of Tuskegee Institute

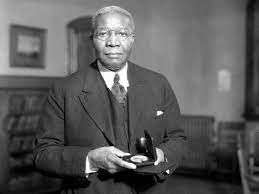

George L Washington, director of mechanical industries and the Tuskegee Institute Division of Aeronautics for the Tuskegee Airmen Training

Tuskegee administrator G. L. Washington realized that the Civilian Pilot Training Program initiative would be the catalyst to provide the basis for establishing an aviation program at Tuskegee, and he played a pivotal role by facilitating acceptance of Tuskegee's application, establishing the program, and then managing it throughout World War II. Two engineering professors, B. M. Cornell and Robert G. Pitts, from nearby Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) provided ground training for the first class. The Tuskegee group were trained at five airfields surrounding Tuskegee, Griel, Kennedy, Moton, Shorter and Tuskegee Army Airfields. A total of 47 officers and 247 enlisted men comprised this groundbreaking group. Thirteen young and talented men made up the first pre-flight training group. Once primary training at Moton Field was completed, they were moved to the Tuskegee Army Airfield, about 10 miles to the west for conversion training onto operational types. Tuskegee Army Airfield became the only Army installation performing three phases of pilot training, basic, advanced, and transition at one military locatio.n Initial planning called for 500 personnel in residence at a time, however, by March 1942 the number ballooned to 3,000. The firm of McKissack & McKissack, the oldest minority-owned architecture, engineering, program management and construction in the U.S., was awarded the Tuskegee contract. The firm was founded in 1905 in Nashville, Tennessee by Moses McKissack, the grandson of a slave, skilled in the trade of making bricks. Moses III, became an accomplished carpenter and eventually teamed with his brother Calvin McKissack to found the company. Moses McKissack was appointed to President Franklin Roosevelt’s White House Conference on Housing Problems. In 1942 the brothers were awarded the Spaulding Medal, recognizing the outstanding Negro business firm in the U.S

Throughout World War II, the primary, basic, and advanced flying training phases were in nine weeks semesters, for a total of 27 weeks of flight training. Contrary to racial beliefs of the time, the first African American flying cadets were college-educated. However, as the needs often do manpower grew greater, high school graduates without college credit were accepted into the program. To help provide some college-level training to those cadets, the 320th College Training Detachment was activated at Tuskegee Institute on 25 April 1943. After five months, graduates of that program were ready to become aviation cadets, and transferred to Tuskegee Army Airfield for preflight training. Of the original 13 cadets accepted for training only five survived the difficult course. The five young men who would make history were Washington D.C. native Benjamin O. Davis Jr, (son of B. O. Davis Sr, the first African American General of any armed forces). Lem Curtis, Connecticut, George Roberts, West Virginia, Mac Ross, Ohio and Charles DeBow, Indiana. One of the most significant episodes for the Tuskegee Airmen occurred the day First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt arrived at the field for a fact-finding tour on behalf of the President. The First Lady was given an thrilling aerial tour of the base by civilian flight instructor C. Alfred “Chief” Anderson. Anderson, who had been flying since 1929 and was responsible for training thousands of rookie pilots. He took his prestigious passenger on a half-hour flight in a Piper J-3 Cub. After landing, she cheerfully announced, "Well, you can fly all right.”

Eleanor/Alfred “Chief” Anderson The Flight Instructor Flying With the Tuskegee Airmen

Col Vance H. Marchbanks Jr.,Flight Surgeon - the Tuskegee Airmen

A varied collection of African American and white flight instructors trained the first African American pilots in American military history. A demanding and rigorous training schedule awaited the Tuskegee cadets. Training consisted of several stages – Preflight (First six weeks were bootcamp followed by four weeks of academics). Cadets were evaluated for 10 hours in a crude flight simulator called a “blue box”, then performed a "ride-along" with a pilot-instructor for an hour. Those that passed were given Cadet Wings and were promoted to Pilot School. Basic – (Cadets were taught to fly in formation, fly by instruments or by aerial navigation , fly at night, and fly for long distances). Cadets got about 70 flight hours in BT-9 or BT-13 basic trainers before being promoted to Advanced Training. Advanced – (This segment placed the graduates in two categories: single-engined and multi-engined. ingle-engined pilots flew the AT-6 advanced trainer. Multi-engined pilots learned to fly the AT-9, AT-10, AT-11 or AT-17 advanced trainers). Cadets were allotted a total of about 75 to 80 flight hours before graduating and getting their pilot's wings. Another first occurrence for the Tuskegee American was the addition of African American flight surgeons. Training of African-American men as aviation medical examiners was conducted through correspondence courses, until 1943, when two black physicians were admitted to the U.S. Army School of Aviation Medicine at Randolph Field, Texas. This proved to be one of the earliest racially integrated courses in the U.S. Army. At that time, the typical tour of duty for a U.S. Army flight surgeon was four years. Six of these physicians lived under field conditions during operations in North Africa, Sicily, and other parts of Italy. The chief flight surgeon to the Tuskegee Airmen was Vance H. Marchbanks J., MD, a childhood friend of Benjamin Davis.

The question at the beginning of this writing asked the question, who were the Tuskegee Airmen? The history of the Tuskegee Airmen has shown us they were undoubtedly, incredible young men who dared to accomplish what society at large, told them what they couldn’t do. And we should never forget stood tall on the shoulders of African American soldiers and sailors who came before them. In addition , they would be an irascible catalyst to advance the struggle for Civil Rights leading to the defining moments of the 1960’s. Many of the Tuskegee Airmen would continue military careers in the newly formed United States Airforce in 1948. Serving in the Korean and Vietnam conflicts in what was once thought impossible, integrated units. Several of these remarkable men who go on to achieve the rank of General Benjamin O. Davis Jr., Daniel Chappie James, Lucius Theus and Charles McGee. Others would turn to academia, medicine, and politics. Case in point, the late Coleman Young, former mayor of Detroit. In essence, the Tuskegee Airmen stood on the shoulders who came before them. And in turn, today activist and military personnel stand on the stand on the broad shoulders of the Tuskegee Airmen

If you enjoyed this informative article, please feel to join my Facebook Group - Evolution Of WW2 Fighter Aircraft

You can now view our store apparel at our Apparel Store